Within one of the LinkedIn groups (sorry, you need to be a member of the “QA Automation Architect” group to be able to read it fully) we started talking about the difference the state of project or product can make for test automation. In this post I will make a distinction between 2 states: new where no code has been written yet and existing where application code has been written, but no test automation has been implemented.

Cutting edge

So when creating a totally new product, life for the testers can be made easier by design, that at least is the thought. This does imply that testers, and not just the “manual” testers but all testers, including automation testers if these are a separate breed as some people seem to think, need to actively participate in the requirements phase of a product. With actively participating I do not mean to imply that they are normally not participating, I mean they need to look a bit further than just at what to test, is it testable etc.

So when creating a totally new product, life for the testers can be made easier by design, that at least is the thought. This does imply that testers, and not just the “manual” testers but all testers, including automation testers if these are a separate breed as some people seem to think, need to actively participate in the requirements phase of a product. With actively participating I do not mean to imply that they are normally not participating, I mean they need to look a bit further than just at what to test, is it testable etc.

They should also use their insights and ideas to help both product owners and software developers to understand what are the things that might make life easier for testing this new product.

When for example building a new web application, they might consider adding a simple REST api to the application, which in production can be closed off based on IP or firewall rules or something like that. A simple REST-API will make life a lot easier when creating your automated tests.

Another thing to make life easy might be ensuring clear and logical naming conventions to be used for all page object in order for the automation to use the Page-Object-Model. Not only is using solid naming conventions good for automation, it also makes maintenance on the application itself easier, since all objects are identifiable by their unique ID.

Legacy

Legacy

How is existing code different from non-existent, other than that one is already in production and the other has to be created? As far as test automation is concerned, especially when talking about legacy software, it may turn out to be a lot more difficult to find proper hooks into the application for solid automation other than on the labels of buttons or fields.

When you have a fairly recent application it may be a website or a desktop app, both have the possibility that there are some sorts of ID’s for all objects. However when talking about true legacy software, such as 15 year old Delphi, it is quite unlikely the developers used WinForms, Win32 or SWT. Not having hooks like that into the application can result in having to scrape the UI for object labels, which is fine when testing one particular language, but if your software was localized things can get even more complicated.

Getting consensus within the technology group about new software is one thing, getting a “non-functional”, non-business related change about in existing software however is a whole different thing.

As long as the code is still “alive”, e.g. new features are still being added, bugs are being fixed and in general there are still developers working on the application, there is hope of getting some more “automatability” in the code.

First of all, while fixing bugs old code is touched, adjusted and retested, this is always an opening to talk to the developers resolving the issue about adding a small bit of extra “sauce” to make it easier to add this particular thing to the automated testing suite to ensure chances of recurrence are minimized, of course by fixing the bug you hope to completely obliterate this particular issue but it might cause new damage elsewhere in the application. So while talking to the developer about this function, try to convince him/her that adding a bit of extra to test not only for the fix of this issue, but also to verify the surrounding features.

While new features are added, this can be treated as “new code”, as long as you manage to get agreement on adding identifiers or a separate layer in these features to make test automation at least easier. If you achieve this, you are quite close to closing the majority of the gap. Refactoring is an excellent opportunity to again make minor changes in the application enabling test automation at a different level.

How do you get “automatability” in your specs?

Assuming you want to get your product easy to automate and thus want to make sure it is thought through, how to get it in the specifications? And more importantly, how do you get it in there without adding things like:

- unnecessary workload

- unneeded and unwanted features

- potential security holes

- un-maintained code

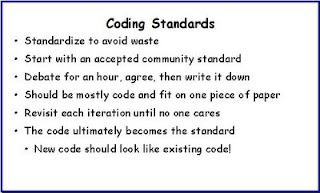

One of the ways to go about it is by, in collaboration with the developers, enforcing a coding standard in which you ensure all objects receive an ID. Regardless of whether it is desktop or web based, most automation tools are looking for a hook into the UI, if there is one, and one of the nicest ways of doing that is simply by using the ID.

One of the ways to go about it is by, in collaboration with the developers, enforcing a coding standard in which you ensure all objects receive an ID. Regardless of whether it is desktop or web based, most automation tools are looking for a hook into the UI, if there is one, and one of the nicest ways of doing that is simply by using the ID.

Alternatively you can have a “layer” put right underneath the UI, ensuring you can bypass the cumbersome UI while automating your tests. One of the issues with this option however, can be that you add “hidden” code which gets forgotten easily. It also is a potential risk for the security of your application, since you basically enable a man-in-the-middle hole.

If this path is taken, ensure that this “feature” does not end up being an opening for malicious code to reach your data. A relatively safe solution for this would be to put some (extra) form of authentication in the layer.

There probably are more options you can investigate, the two I mention above are fairly harmless and yet can make life in test automation a lot easier and predictable.

In the end, no matter which way you go, as long as you get both developers and product owners on board in working towards a higher “automatability” of the code life for you as a test engineer could become a lot more fun.

I am not very impressed with theological arguments whatever they may be used to support. Such arguments have often been found unsatisfactory in the past.

Alan Turing

A graph like this contains a lot of information so it will need a bit of explanation when showing to the team and especially to managers. On a per sprint basis this graph shows:

A graph like this contains a lot of information so it will need a bit of explanation when showing to the team and especially to managers. On a per sprint basis this graph shows: